I'm a startup engineer; 3x first engineer, former Uber engineer, and have worked at many more startups.

In this article, I cover how I orient around operational processes, when to invest time in them, and when to not.

Modes of transportation

An operational task is a task that emerges from running a business (e.g. generating reports, onboarding customers, setting up a server, making donuts).

Each of these tasks has a time cost associated with it (time to do the task) as well as the amount you've invested to make it faster (time and/or money).

I like to reframe the investment as a mode of transportation. e.g. If we invest 4 hours into building a bike/car/rocketship/etc for this task, is it worth it?

To reiterate, these investments are usually independent from each other, so a rocketship for generating reports is unlikely reusable for setting up a server.

Aside: One of my engineering values is velocity (internal and external perception), so it makes sense that I lean into this analogy.

Pain tolerance

Let's zoom in on an example recurring task. We're going to start with a contrived example but will have real-world examples at the article end.

At Company X, they're a sales-oriented company and manually perform account creation to onboard a new customer.

On the side with no time invested, we have the "slow and painful" version:

- Sales finishes signing a contract with Customer

- Sales notifies Engineering of the new registration

- Engineering has no documentation, reads through code, figures out the commands, and thankfully nothing goes wrong

- Partway through Engineering realize they're missing a critical field (e.g. database color) and notifies Sales

- Sales reaches out to the Customer

- Customer replies to Sales

- Sales notifies Engineering

- Engineering completes onboarding and notifies Sales

- Sales notifies Customer

On the side with maximum time invested, onboarding is "fast and easy":

- Customer signs contract, a webhook is triggered (set up by Engineering)

- The webhook creates an account and sends an invite link to the Customer to self-serve onboard themselves

If you're an empath with low pain tolerance for monotony, then the "fast and easy" version should feel a lot better from the perspectives of yourself, the rest of your team, and the customer.

If you don't feel this, then this article probably isn't for you =/

Incremental improvements

So why did that first one feel so bad, what can we can we improve, and when can we find time to improve it?

Why it felt so bad: It was monotonous (sometimes "hurry up and wait", sometimes we've done it 100x before) as well as stressful (e.g. easy to typo a command).

As for the other 2 questions, let's think about incremental improvements to get to "fast and easy", as well as how much time they'll take.

Runbooks and note taking

The biggest impact low hanging fruit is that Company X hasn't yet invested in the fundamentals around documentation.

In this scenario, I would take notes during the process, then clean up the notes afterwards for consumption by others. This form of documentation is called a runbook or a workflow.

By doing this, we now have commands to copy/paste, thus stress less and spend less time about getting code right next time.

Additionally, we've established a convention for the rest of the company to adopt. e.g. Sales + Engineering can create a runbook to verify all fields are filled in before handing off to Engineering, thus eliminating steps 4-7.

The new process now looks like:

- Sales finishes signing a contract with Customer

- Sales goes through the Sales Onboarding runbook, verifies no issues, and notifies Engineering of the new registration

- Engineering steps through the Engineering Onboarding runbook and copies over commands

- Engineering completes onboarding and notifies Sales

- Sales notifies customer

Q: What about a one-off process, like a report?

A: I'd argue that documenting steps as you go still has its benefits. It communicates to others what you did (catch issues + education) and allows reuse if it's not a one-off after all.

Q: Why would I do this instead of scripting?

A: Sometimes you're under a very tight deadline, and writing a script has additional (often forgotten) time costs. For example, authoring tax (testing, usage documentation) and maintenance tax (e.g. schema changes).

Scripting

The next improvement is scripting, i.e. creating a CLI utility to automate what's being done in the runbook.

This has a much steeper time investment than a runbook, but it's also the first step to abstracting Engineering from an operational task (i.e. if core written modularly, then can easily repurpose code).

Some additional benefits are: We can be more confident in conditional logic, accept configuration parameters, and add testing (if desired).

The new process now looks like:

- Sales finishes signing a contract with Customer

- Sales goes through runbook, verifies no issues, and notifies Engineering of the new registration

- Engineering runs the account creation script

- Engineering notifies Sales

- Sales notifies customer

Internal tool

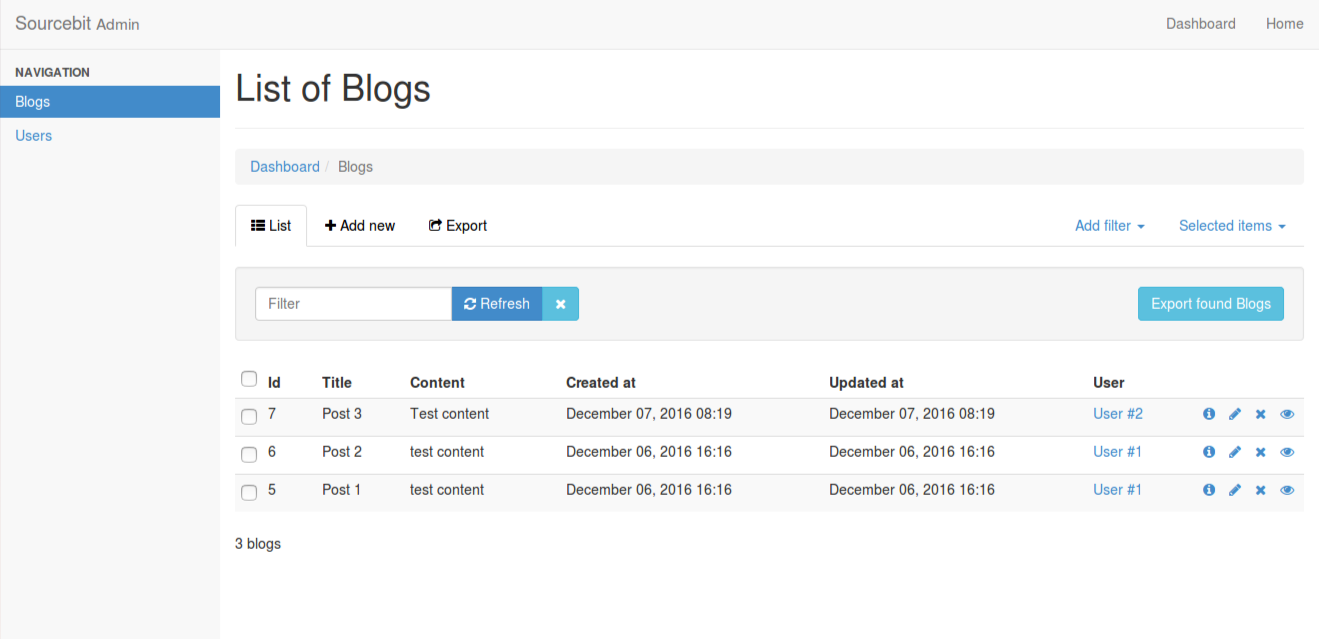

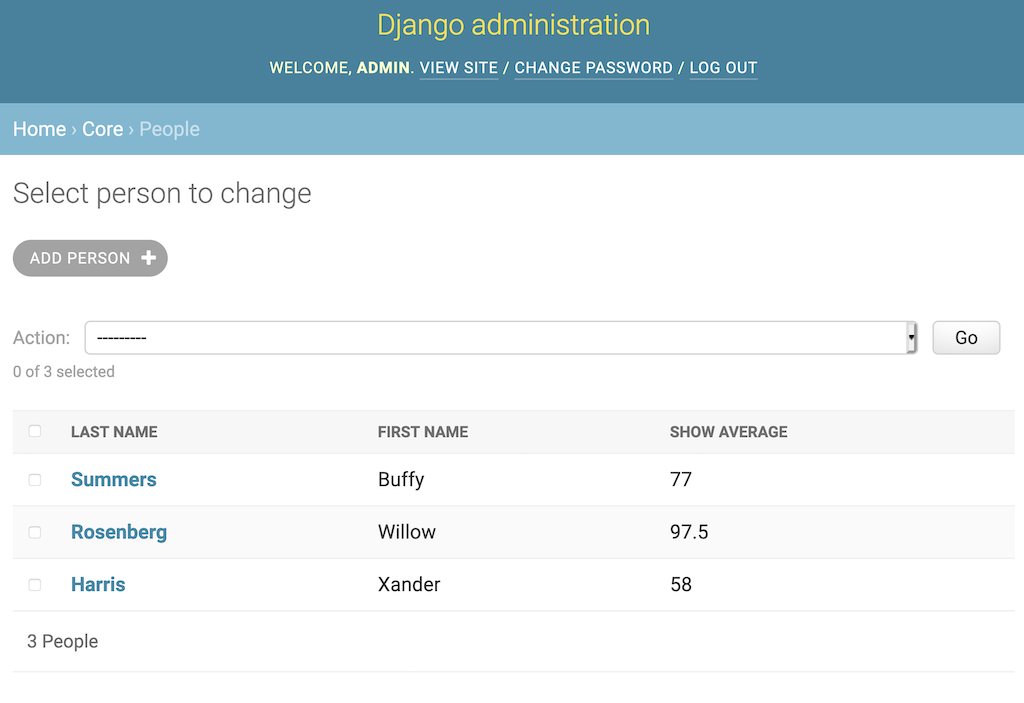

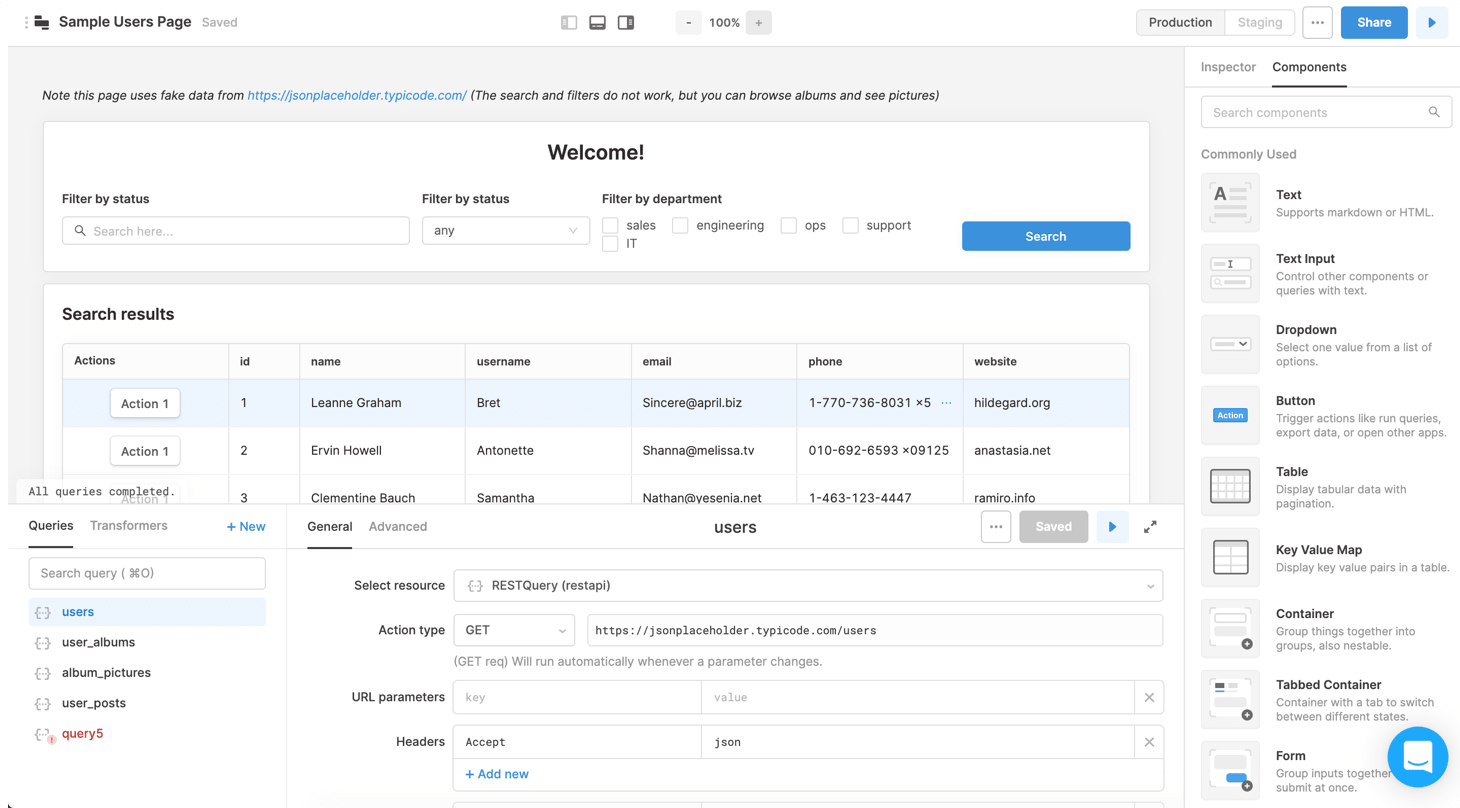

An internal tool is an employee-only site to look up internal data as well as perform common actions. Examples include:

I have mixed feelings about Retool. While it's powerful, writing directly to a DB bypasses business logic. If you use it, interface with an internal API.

While it's possible for a startup to get by without an internal tool, it's another fundamental investment that pays massive dividends by removing Engineering as a bottleneck.

For our incremental improvement lens, the next step would be to mold our script into an action in the internal tool.

The new process now looks like:

- Sales finishes signing a contract with Customer

- Sales navigates to internal tool and onboard the customer

- Sales notifies customer

Q: What about similar yet different nuanced reports?

A: This is another form of internal tool, known as Business Intelligence (BI). I've seen this take the form of SQL queries (e.g. Redash, Mode) as well as higher-level abstractions (e.g. Metabase).

Q: What about engineering-only tasks?

A: The internal tool here might be GitHub Actions, Jenkins, ChatOps, or something else along these lines.

Self-serve

The next step is to remove Sales from the process by integrating into when a contract is signed.

This could be a push-based system (e.g. receive a webhook), a pull-based system (e.g. on a cron, query for status change), or something bespoke to the relevant integration.

The new process now looks like:

- Customer signs contract, a webhook is triggered (set up by Engineering)

- The webhook creates an account and sends an invite link to the Customer to self-serve onboard themselves

No implementation

One additional option to consider is if the process is needed.

Onboarding is obviously needed, but what about a one-off report or a feature that's going away soon?

By building exactly what you need, you save both the time invested as well as time spent doing the action.

Jumping between levels

In each of these increments above, it seems very linear in order (i.e. Write a runbook then port to a script then ...). However, that would be rather wasteful of time if you just need self-serve immediately for the best user experience.

In your considerations, factor in the costs and payoffs for each of these levels from where you're at currently, as well as the effort again to move to the levels after that.

When to invest in the next step

Like many business decisions, this is a cost vs value decision.

On the cost side, each level depends on:

- Your infrastructure (e.g. does internal tool exist yet?)

- You and your coworkers' experience adding to this system

- Time availability to do this upgrade (i.e. by choosing to do this, you're choosing to not do something else)

- Is there a hard deadline on this task? Would failing to finish on time jeopardize something?

- Other heuristics specific to your company

On the value side, we consider:

- How frequently do you think this is going to be run?

- How much of a burden is running the task to other teams? (e.g. is there some common associated support ticket?)

- How does it affect the user experience? (e.g. would automating decrease churn or increase conversions?)

- If you invest all this time, and the startup pivots (these usually come out of nowhere), is there still reuse after this?

- For pivot timing, I usually try to predict 6 months into the future. Anything beyond that is usually impossible to guess

One heuristic I usually lean into is "pain tolerance". If it starts to become painful to do on a regular basis, then I set aside time to automate further. One coworker phrases this as "do it until it hurts", another common phrase is "do things that don't scale".

Q: If I'm unable to prioritize for this, then what do I do?

A: Ideally everyone has an equal voice at your startup. If not, that might be a sign of deeper cultural issues.

That being said, sometimes we still need to find time to carve-out. I sometimes categorize these under "fix as you go" but communication and allocation is much more ideal.

Time estimation

While this article isn't going to dive into better time estimation techniques (short version: walk through code + think out what needs to be done), it's probably valuable to have some context on reasonable expectations.

Here's estimates I'd give for a task that takes 30 min to 1 hour (including 15 min context switching):

- Running commands by hand with a runbook: 30 min to 1 hour

- No additional time for copy/pasting to runbook as I go

- Writing a script: 2-4 hours + light maintenance tax

- 1 hour for commands + 1 hour for CLI testing + 2 hours buffer for issues that arise

- Maintenance tax: Maintaining through schema changes and CLI flag changes

- Internal tool: 3-5 hours + light maintenance tax

- 1 hours for command + 1 hour for integrating into tool + 1 hour for testing + 2 hours for buffer

- Maintenance tax: Maintaining through schema changes and form submission changes

- Self-serve: 6-10 hours + heavy maintenance tax

- 1 hour for command + 1 hour for integrating into endpoint + 2 hours for building UI + 2 hours for integrating with webhook + 4 hours for buffer

- Note: This also creates UI for the end-user, so there's likely a conversation you should have with coworkers around UX

- Maintenance tax: Maintaining through schema changes, form changes, UI styling, and UX flow changes

- No implementation: 0 minutes since there's nothing to build 🎉

Real-world examples

Weekly batches

At Underdog.io, a curated job seeker <-> company marketplace, we'd send out weekly emails with a new candidate batch to companies.

The initial setup was:

- All sign-ups added to a Google Sheet (explanation in "Lessons of a startup engineer")

- Curation was done in an internal tool, but ratings were written by hand back to the Google Sheet

- To generate weekly emails:

- Each company receives a custom email due to candidates opting out of specific companies (e.g. current employer)

- Cofounders copied/pasted new candidates to per-company spreadsheets

- Manually filter out candidates based on company

- Copy into email and send to specific company

This was fantastic for proving we were a viable business without major time investment. Eventually though, founders were taking full Sundays to perform this task so automation was desperately needed.

Additionally, there was always a risk of sending a candidate to a company they opted out from (e.g. typos happen).

So, improvements were high value and thus high priority:

- First, we brought email generation into our internal tool

- This is a jump from: an unwritten runbook to internal tool

- Next, we added safeguards like string distances to derisk any accidental opt-out misses

- Last, we moved remaining Google Sheets interactions into the internal tool, then migrated to PostgreSQL

- This maintained value and eliminated the risk of unintentional data modification/loss

We stopped short of automating email sending, because we still wanted the human touch as well as building trust in the automated system.

Nowadays, there's a dashboard for companies to visit any time they'd like.

Server setup

This is an example of when automation goes too far. i.e. Setting up a new server for a low-traffic early stage startup should only be logged as a runbook, not automated further.

However, my naive self hadn't learned these lessons yet and did:

- Full-on automation for twolfson.com (this site) via Chef

- Reused that same setup for Find Work

- At Standard Cyborg, we wanted HIPAA compliance so we migrated to AWS but also built a very robust Terraform setup

As one might imagine, these were fantastic to build and understand. But when you come back to it months later to adjust things (e.g. upgrade Node.js), it has a massive maintenance tax from being out of mind and relearning it adds little business value.

Thus, a runbook would have been significantly easier to generate as well as maintain.

Scan processing

At Standard Cyborg, a 3D scanning and prosthetic CAD platform, we'd sometimes receive infrared (IR) scans that wen't fully filled in.

This is due to the IR scanner collecting a point cloud and trying to determine faces from nearby vertices. However, this wasn't its specialty, so we'd use tools like MeshLab to clean up any gaps or double layers.

As with weekly batches, there's significant time cost but also rushes of scans can come in (e.g. during a convention). Most importantly though, scan cleaning can be emotionally taxing (e.g. scans with traumatic injuries).

Thus, automation was a high priority for us, and the result was moving manual actions into scripts in an AWS Lambda pipeline.

After that, employee happiness increased significantly as well as there now being freedom to focus on higher level tasks.

Additional short list

- Deployments - These occuring regularly, so scripting is critical

- Investing into Continuous Delivery (CD), since you also need a robust migration and rollback system

- Database dumping, scrubbing, and pruning - Any level of automation makes sense here. Likely depends on frequency and monotony

- Firefighting and deployment rollbacks - Ideally these never happen but that's not reality, so a core runbook is a great starting point

What we didn't cover

- Feature prioritization - This usually isn't owned by engineering

- Short version if you're curious: metrics, requests by customers, impact on churn or conversions

- Day-to-day prioritization - Sadly made the article too long

- Short version:

- Address blockers first (e.g. PR reviews, ongoing discussions)

- If have bandwidth, triage any new bugs

- Weigh tasks into a queue (e.g. those with due dates vs other important tasks vs current bandwidth)

- Take the next task from said queue

- If an interruption occurs, triage and/or delegate

- Upon task completion, reprocess queue and start next task

- At end of day, address any blockers again

- How this ties into the relevant xkcd

- Short answer: It's the "how" for each of the different levels

- Longer answer: Our article isn't purely about time. Other factors include UX, employee happiness, and more

Additional reading

Feedback form

- Investing into Continuous Delivery (CD), since you also need a robust migration and rollback system

- Feature prioritization - This usually isn't owned by engineering

- Short version if you're curious: metrics, requests by customers, impact on churn or conversions

- Day-to-day prioritization - Sadly made the article too long

- Short version:

- Address blockers first (e.g. PR reviews, ongoing discussions)

- If have bandwidth, triage any new bugs

- Weigh tasks into a queue (e.g. those with due dates vs other important tasks vs current bandwidth)

- Take the next task from said queue

- If an interruption occurs, triage and/or delegate

- Upon task completion, reprocess queue and start next task

- At end of day, address any blockers again

- How this ties into the relevant xkcd

- Short answer: It's the "how" for each of the different levels

- Longer answer: Our article isn't purely about time. Other factors include UX, employee happiness, and more