Remembering is a practical skill. It's part of our daily routines (e.g. remembering a grocery list, remembering to ship a package).

The opposite of remembering is forgetting. For the purpose of our discussion, I want to consider controlling forgetting as a practical skill. When we forget something, it is released from our cognitive load and makes space for something new. For example:

- Allows thinking about other topics (e.g. reflecting on past events)

- Relieves mental stress (e.g. juggling thoughts)

- Offload a thought/action for later (e.g. setting a calendar reminder)

Notices:

- This is all based off of personal experience with no rigid science

- While it might sound like we are discussing unlearning, we are not. Unlearning means removing something entirely from your memory. Forgetting means placing something to a less active part of our memory.

Table of contents:

Background/Common knowledge

Remembering an item/set of items for later

This is a canonical example of practical forgetting. We have a list of things we want to remember for a later time but it's impractical to keep on thinking about them now. These can be tasks (e.g. visiting the doctor, writing a blog post) or tangible items (e.g. buying specific groceries).

Depending on the situation, there are a few different solutions:

- To do lists; a check list of items to purchase/tasks to be done

- This is most practical for multiple items

- Notes; text describing a task or set of tasks at hand

- This is practical for single items

- Depending on the thought, more/less words will be applicable (e.g. a sentence fragment to many paragraphs)

In these solutions, the medium can vary depending on the situation (e.g. electronic is good for reuse/sharing, paper is good for attaching to a specific location like a desk).

Personal solutions

Forgetting when falling asleep#long-term-context-loss

When falling asleep, sometimes I have epiphanies about the past day or upcoming tasks. No matter how hard I try, I almost always forget these when I wake up. Additionally, if I begin to think about finer details, then I start to lose track of the original thought and lose everything.

I deal with this by keeping a paper notepad and attached pen next to my bed. When I have a thought I want to remember, I:

- Sweep around the general area where the notepad is until I find it

- Take out the pen, uncap it, and place it on the back of the pen

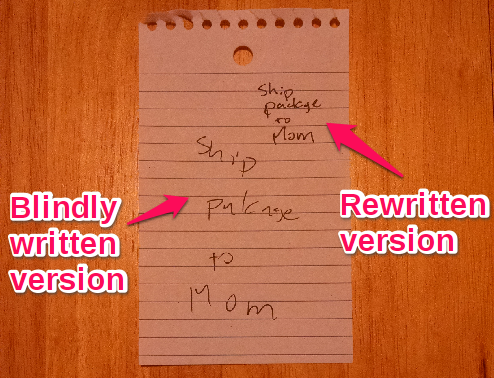

- Blindly write down the thought on the paper in the dark

- Rip off the sheet of paper

- Put the pen back together and reattach to the notebook

- Put the notepad back in its area

Once the thought has been written down, I let my mind drift and it begins to think about other topics. If I think of something else that I want to remember, then I write it down again.

Note: Perform this in the dark and with a notepad because any light will stop melatonin production and prolong not falling asleep.

In the morning, I read the note and the thought rushes back into memory. Then, I rewrite it (usually it has some typos or scribbles), and then consider this note as the same from our "Remembering an item" section.

Suggestions:

To reduce the likelihood of illegible notes, I have a few suggestions:

- When writing down a word, remember the shape of the letters and draw those

- Sometimes when half-awake, my wires get crossed and I write gibberish letters unless I do this

- Rewrite the note in as soon as you wake up. Thoughts that seem fresh now might be lost later (kind of like with remembering dreams).

Remembering on the go

Whenever I leave the house, I usually bring a pen. Sometimes I find myself in a situation where writing a note via pen on my wrist is my best option at the time.

- When I don't have paper or my phone isn't easily accessible

- When I am walking and need to remember a task (e.g. commuting and need to ship a package)

Tip of the tongue moments

Whenever I had a fleeting thought that I know I am going to forget shortly due to other larger tasks, I always take time to write it down.

As with the past techniques:

- Write it down either on paper, electronically, or on your wrist via pen

Splitting mental space for personal and work

Thinking about work tasks while you are in your personal life can be unnecessarily stressful. Often they are tasks that you are unable to do at the moment and you already know what needs to be done.

As a result, I try my best to keep personal things personal and work things for work.

When working:

- Avoid checking personal email as it will remind you of stressing other tasks that you have in your daily life

When working remotely:

- Never directly context switch between work and personal tasks

- Always do something between them. For me, I sleep my computer and go get dinner or take a walk.

When not working (e.g. personal life):

- Avoid checking work email as it will remind you of stressing other tasks that you have in your daily life

- Push notifications for email are a really bad habit and will cause unnecessary stress

- Instead, feel free to check work email when you have downtime and can actually facilitate any issues

- If you are an engineer, try to set up something like Pager Duty which will call you about the immediately important things

Personal experiences

Long term context loss

Programming

Programming

Due to being active in open source for a while, occasionally an issue will open on an older repo and I will have to refresh my memory from it. From this experience, I have learned some good practices to embed in repositories:

- Always write practical comments inline

- Writing lots of open source that you re-read later helps you get better at this

- Always write documentation and use it immediately after

- Getting familiar with your repo is very painful if you can't remember anything about it (e.g. reasoning, signatures)

- Communicating with your future self is just as practical as communicating with future developers

- Getting familiar with your repo is very painful if you can't remember anything about it (e.g. reasoning, signatures)

Taking a break in Japan

When I was taking a break in Japan, I did my best to step away from programming as much as possible. There were a few open source issues that snuck through but when handling them, I noticed a few things.

- I had very little forward thinking (e.g. I couldn't reason about how an API would expand and handle edge cases)

- Naming variables normally comes more easily after writing code for a while (read as a little slow but not super slow)

- However, when on break, I was super slow with naming due to nothing coding relevant being mentally active

When I got back and resumed programming normally, it took a couple of days to get back into the swing of things.